The Big 5 - Municipal Housing Platform

Introduction

Toronto is in a housing crisis and it's no accident. Decades of bad policies from municipal governments have stoked housing demand while suffocating supply. Housing prices have skyrocketed, renters are competing for availability, and people are leaving the city. "Drive until you qualify" exurban sprawl is making commutes longer, baking-in car dependency, and increasing carbon emissions. The housing crisis segregates the city, where only those with wealth or who inherit wealth can afford to live in Toronto. The housing crisis is an everything crisis.

According to recent reports by the Smart Prosperity Institute and the CMHC, Ontario needs to build at least 1.5 million and up to 2.6 million new homes over the next decade to restore affordability. We know we need to build a lot more homes, and we know the policies to get there. At the same time, if we are committed to the principle of housing as a human right, the government needs to increase investment in affordable housing for people who will not be served by market-rate housing.

In December 2022, City Council approved the 2023 Housing Action Plan (HAP) which we believe is a good start. However, nothing concrete from the plan has been proposed. Getting the implementation details right will be essential. In the past, City Council has watered down pro-housing policies, for example, by imposing minimum parking requirements for rooming houses or prohibiting two front doors for secondary suites. This cannot keep happening. In the upcoming election, we expect many candidates for mayor will commit to achieving overall housing production goals or following through with the HAP in principle. However, reality has often been the enemy of principle in housing politics, and that’s why true pro-housing candidates will distinguish their commitments with specific policy actions needed to get these homes built and end the housing crisis.

Our platform contains what we believe to be the most important municipal policies to end the housing crisis. For a more comprehensive set of recommendations, we encourage you to read the Housing Affordability Task Force report and our submission to the Housing Affordability Task Force. We encourage you to use our platform and ask candidates for mayor directly if they support these policies, so you can make the most informed vote possible.

Exclusionary zoning in Toronto

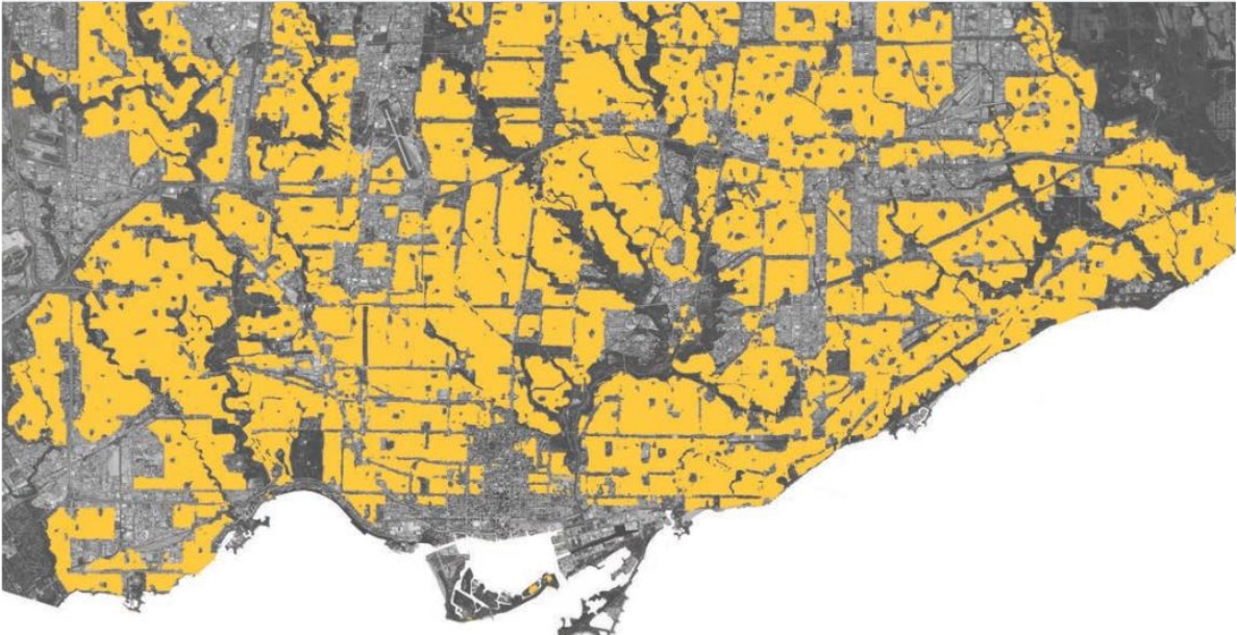

Past Toronto city councils have set aside the vast majority of Toronto's residential land as "stable neighbourhoods" that are not planned to grow.

1. Legalize Housing For All

It's time to end exclusionary zoning by:

- Legalizing construction of four storey 6-unit multiplexes across the city as-of-right.

- Permitting low-rise and mid-rise apartment buildings as a minimum as-of-right zoning permission on neighbourhood main streets, local transit routes and in the interior of wealthy neighbourhoods well-served by local transit.

- Permitting high-rise apartment buildings as a minimum zoning permission within Major Transit Station Areas (MTSAs).

- Expanding mixed use areas up to 250 metres from Avenues where up to six storey buildings are legalized as-of-right.

- Allowing more mixed-use and small businesses in residential neighbourhoods.

The vast majority (66%) of residential land in Toronto is zoned for single-family homes, the most expensive and least environmentally-friendly housing type. The population of these neighbourhoods has decreased over the past fifty years, even though Toronto's population has grown as a whole. Young people today cannot afford to stay in the neighbourhoods they grew up in. Consequently, parents are unable to live near their adult children (and grandchildren). Seniors are unable to downsize within their neighbourhoods. Immigrants must live in poor conditions far away from work or school to make ends meet. We can provide more housing options for people to live in if we permit more types of homes beyond just single-family detached houses. This starts with ending exclusionary zoning to legalize homes that people can afford.

Zoning should be permissive rather than restrictive. Allowing mixed-use and multi-tenant homes is an important first step to make housing attainable and affordable again in these neighbourhoods. The city’s own reports have found neighbourhoods with more permissive zoning to be much more diverse than those with less permissive zoning. Increasing density and housing options comes with a host of other benefits. They foster complete, inclusive neighbourhoods for pedestrians, cyclists and transit users and reduce car dependency. Subway stations, LRT stops and GO stations provide opportunities to build high-rises and other housing (market and affordable) and decrease carbon emissions. Enabling more multifamily housing types made from wood comes with lower construction costs, faster building times, and lower embodied carbon emissions. In this view, mixed-use apartment buildings should be permitted much more broadly in Toronto.

2. Make Rules That Make Sense

Reform policies that thwart much needed housing and result in worse urban spaces by:

- Eliminating arbitrary urban design guidelines like floor space index (FSI), angular planes and floor plate restrictions to promote more housing, larger family-oriented units, and more functional unit layouts.

- Removing references in the Official Plan that require that new housing match the existing physical character of the neighbourhood.

- Reserving heritage designations for buildings that are truly unique and ending the practice of bulk inclusion of multiple sites into the heritage register.

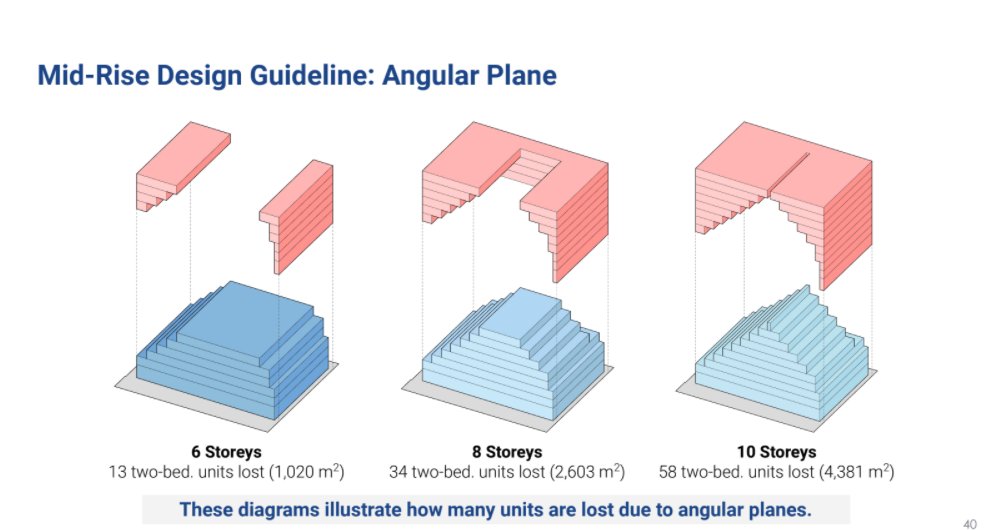

- Eliminating minimum parking requirements for multi-tenant homes

We desperately need more housing in Toronto, but a host of planning policies and "urban design guidelines" make building new housing the last priority. These design guidelines, routinely treated as requirements, reduce the amount of housing built in favour of subjective aesthetic choices that in many cases result in uglier architecture. For example, a report by students at the Toronto Metropolitan University School of Urban Planning's studio class in collaboration with HousingNowTO found that the application of the angular plane urban design guideline resulted in an increase in construction cost and a reduction in the number of homes built, all in an effort to prevent shade. This drives up housing costs for the buyers and renters of those new homes, worsening affordability. Design guidelines should be amended to align with the city's priorities. It’s time to focus on housing, green energy, sound and thermal insulation, affordability, and architectural quality.

Wanting to preserve the character of neighbourhoods is understandable: we love what makes our communities great and unique. However, when physical character is prioritized in policy over inclusivity and diversity, actual neighbourhood character is lost. Neighbourhoods that used to house people of all ages, from young children, to seniors, have lost their character as families with children under the age of five migrate out of Toronto in the thousands towards exurbs even farther than the 905 region. While architectural character may be preserved, the community character has become a hollowed out memory. People make the character of a neighbourhood, not the buildings. To truly preserve the character of our neighbourhoods, we need to rebalance policies that prioritize physical character over all else.

3. Build Affordable At Every Opportunity

Prioritize affordable housing by:

- Including affordable housing in every city-led development, such as libraries, community centres, and new subway stations.

- Redeveloping public land, such as Green P parking lots, for affordable housing.

- Expediting zoning and official plan amendment approvals for non-profit affordable housing developments and exempt them from urban design guidelines and other restrictive planning policies.

- Following Inclusionary Zoning principles that incentivize and provide offsets for affordable housing through development charge waivers, density bonuses, and parkland fee waivers.

- Leveraging opportunities for capital investment in affordable housing stock, such as implementing policies creating access to the Federal Government’s Housing Accelerator Fund (HAF)

Many city-led developments – fire halls, EMS stations, libraries – are built at a low-rise scale, without any housing. This is unacceptable in a housing crisis. A new one-storey library with no affordable housing on top must be the exception, not the rule. Every new community centre, Green P parking lot, and library is an opportunity to deliver publicly-owned affordable housing.

Affordable housing is a necessity that is becoming increasingly scarce, as it is incredibly expensive to build and maintain. Toronto must create the conditions for affordable housing to be economically feasible at scale to tackle ever-growing backlogs. Non-profit developers face the same barriers to building as for-profit developers – lengthy zoning approvals and restrictive urban design guidelines – but they also have a harder time financing their projects. We need to support our affordable housing builders with direct funding, density bonusing, expedited approvals (including requests for Minister's Zoning Orders from the province), and relaxed urban design guidelines.

When it comes to including affordable housing in private development, we cannot ignore the economic realities of building housing. Construction, operation, soft costs, and risk are through the roof, while approvals take years and are not guaranteed. At the same time, opponents of new housing developments often tout magical math, asking for reductions in height and density, while at the same time demanding affordable housing be included alongside other community benefits. The financial reality of housing development means that any reduction in density makes it difficult, or even impossible to include affordable housing. Affordable housing must be the first priority over other requests to developers. We need to allow greater density, offer expedited approvals, relax urban design guidelines and provide financial incentives for developments that include affordable housing.

Inclusionary Zoning (IZ), where the city mandates that a certain proportion of a new housing development be set aside as affordable housing, provides an opportunity for more affordable housing. However, without government support in reducing costs, those costs will be passed on to market rate homes, further exacerbating housing affordability. An even worse scenario is increased costs delaying or even stopping new housing projects outright, resulting in even greater pressure on the existing affordable housing stock. This is not unprecedented: after implementing inclusionary zoning without any compensating incentives, Portland saw the number of permits issued for apartment buildings drop by 60%. We must avoid replicating this scenario in Toronto by using a carrot-and-stick approach to make IZ successful: providing expedited approval timelines, allowing greater density for more affordable housing, and giving financial incentives. These incentives should be crafted for all new housing and apply to every property in the city, so that affordable housing options are possible in all neighbourhoods, not just in major transit station areas.

4. Ensure Consultation Reflects Communities

Reform when, how, and whether we consult by:

- Providing digital options for every public consultation.

- Using channels outside of the traditional public meetings that tend to be accessible for those privileged to have time to attend.

- Saving on planning costs and councillor time by eliminating public consultation meetings for medium-sized and smaller projects, and for Committee of Adjustment applications.

- Considering future residents whose voices are not heard.

- Considering equity, accessibility, and representation, especially for those with the greatest need for housing.

An in-person public consultation

Before COVID, in-person consultation was usually the only option provided. Without providing other options, these consultations failed at attracting diverse voices, being accessible, and considering the opinions of future residents.

Today's version of public consultation elevates the voices of the wealthy and privileged, who have the time to attend meetings at 5pm or 7pm, week after week, in a high school gym or church basement. This version of local democracy favours an older, wealthier “leisure class” with time to participate rather than reflecting the will and needs of the city as a whole.

Over the past two years, virtual options were provided for every consultation, making them more accessible to young parents, those with accessibility needs, and future residents. It is essential that digital options continue into the future in a hybrid or online-first public consultation format. When consulting, the City should also meet people where they're at and proactively seek out diverse voices, through canvassing busy transit stops, neighbourhood community centres, and even going door-to-door.

Public consultation meetings on their own are a significant time commitment and monetary expense for city planning staff, councillor staff, engaged community members, and the councillors themselves. There is no reason to hold a public consultation meeting for every new midrise. Local community members can always email or call the planner in charge or their local councillor with their concerns if they have any. Public meetings should be reserved for truly large and unique projects, and large-scale changes. This way, they will be easier to publicize for a broader audience, and draw a more diverse set of people and viewpoints.

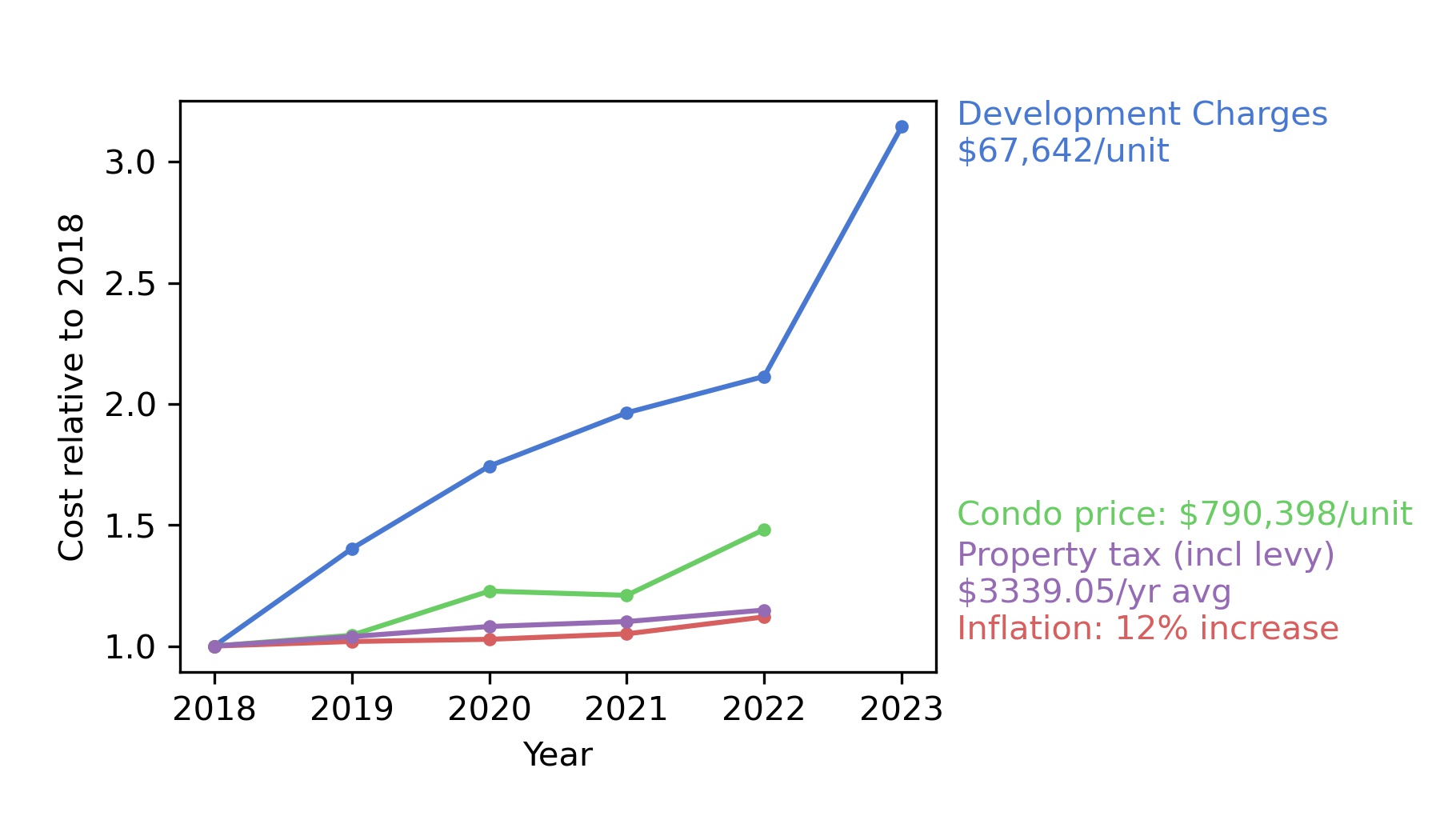

Development charges pick up the slack

The current city council has tripled development charges since 2018, even though development charges had already increased 600% since 2009. Meanwhile, average property taxes have barely budged.

5. Tax Fairly And Sustainably

Tax more fairly by:

- Aligning property tax rates for single-family and multi-family homes.

- Limiting development charge and parkland dedication increases.

- Exempting the first four units from development charges.

- Advocating for a land value tax and exploring other revenue tools.

- Studying tax-to-service burdens of different property types.

- Studying parking levies on commercial surface parking lots to encourage development.

Toronto needs to increase its revenue to be able to invest in affordable housing and world-class infrastructure for our growing population. Toronto currently maintains the lowest property taxes in the province, maybe even the country, all while having new residents pay a larger share of the costs in the form of development charges, land-transfer taxes, and inequitable property tax classes. For instance: people living in multi-residential buildings built before 2017 pay a higher property tax rate than people living in single-family homes despite having less wealth, renting instead of owning, and living in high-density buildings that are cheaper for the city to serve. The property tax rate for general residential should be aligned to match that of older multi-family buildings.

Toronto should shift away from development charges (DCs) as a significant revenue tool. It’s easy to see DCs as just a tax on a developer’s profits, but that framing ignores just how many housing projects become unviable under high DCs. Missing-middle and affordable projects are the first ones to get cancelled when DCs and borrowing costs rise in tandem. When DCs are raised across the board, they increase the scarcity and cost of housing, only favouring existing homeowners who reap the benefits of growth without paying anything for it. The city uses the mantra of “growth must pay for growth” to set and raise DCs, which casts growth in a negative light as a net expense for the city and not an investment in its future - both in the tax revenue it will generate and in the people it will bring to Toronto.

The city should advocate to the province for a land value tax. Compared to our current property tax system that taxes land and improvements, a land value tax taxes the unimproved value of land. Hence, property owners would not be penalized for making improvements and building on their own land, and would be encouraged to build more housing to make the best use of their property. A land value tax also cracks down on landowners and developers who speculate on empty lots increasing in value. Additionally, land value taxes cannot be passed on to renters, while property tax can. Land value taxes are known to be the most economically efficient and equitable taxes available to governments.

The city has other revenue tools it could instate on its own, or advocate to the province for. Municipal leaders should advocate for more tax options, such as levying a point of HST or implementing vehicle registration taxes, congestion taxes, freeway tolls, and gas taxes. These new revenues could all play a major role in funding Toronto’s future without disproportionately burdening an already-overburdened generation of new Torontonians.