Read The Full Analysis Here: http://www.erikdrysdale.com/DA_kramer/

About Erik

My name is Erik Drysdale and I work as a Machine Learning Specialist at the Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) for the AI in Medicine (AIM) initiative and the Goldenberg Lab. My professional responsibilities include the development and training of the machine learning models for various pediatric data science projects. My research interests are focused on the intersection of statistics and machine learning methods such as high-dimensional inference, survival analysis, and optimization methods. I also have a background in economics and I worked as a housing economist at the Bank of Canada.

Executive Summary

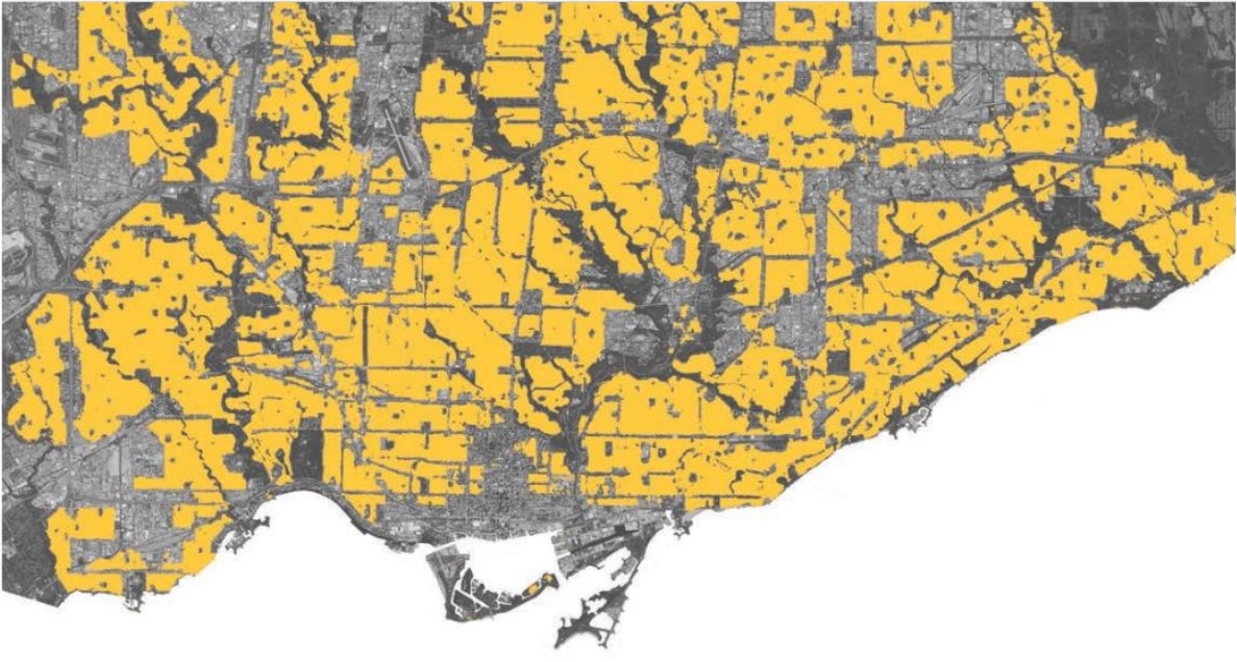

Because this analysis contains seventeen figures and numerous technical discussions, I have distilled the salient facts which emerge from the analysis. Despite the impressive gains in population in these two cities overall, the distribution and composition of neighbourhood growth in the Toronto and Vancouver CMAs is skewed and limited to a handful of areas. The clear spatial and geographical concentration of population increases points to obvious regulatory constraints preventing densification on the majority of residential land.

- Over a 45 year period, 1971-2016, 56 of Toronto’s 140 Official Neighbourhoods had smaller populations in 2016 than they did in 1971 (e.g. The Annex). More than 70% of Neighbourhoods in what was formerly Old Toronto, fall into this category of de-densification. 80% of the City of Toronto’s population growth have come from 20 Neighbourhoods.

- The Toronto and Vancouver CMAs have seen their population more than double since 1971, outpacing national growth, and adding 3.2 and 1.4 million individuals, respectively.

- The City of Surrey accounts for the plurality of growth in the Vancouver CMA (31%). Growth is more balanced between the City of Toronto and the other municipalities that make up the Toronto CMA.

- Two-thirds of the Toronto CMA’s population growth has come from the creation of new DAs, and only one-third of population growth has come from increasing density of existing DAs. In the Vancouver CMA, the figures are reversed: two-thirds of the population gains have come from increased densities in existing DAs.

- Since the 2011 census, very little population growth has come from new DA formation.[1]

- Toronto’s oldest DAs have shown very little densification, whereas DAs formed after 1971 have been more likely to record higher densities over time.

- Roughly the same number of DAs lose population compared to those that gain. De-densifying DAs lose an average of 250K and 125K individuals between census years in the Toronto and Vancouver CMA, respectively. However, the net gains from density to each CMA end up being positive as the DAs that see population growth increase by a larger magnitude than those that see population declines.

- There is a clear spatial correlation for those areas that have seen population density increase or decrease. Population growth has been concentrated into a fraction of residential areas.

- Statistical evidences suggests that having a higher share of row housing units is associated with higher population growth (the “missing middle” hypothesis), whereas higher incomes and single-family and semi-detached homes are associated with a declining population over time (the NIMBY hypothesis).